The 1924 Family Dinner That Changed Home Canning Forever

Every generation has its stories — the ones whispered around kitchen tables to remind us that food preservation isn’t something to take lightly.

One of the most sobering comes from Albany, Oregon, in the winter of 1924, when a simple family dinner turned into one of the most heartbreaking food safety tragedies in American history.

Inside this post:

A Family Dinner That Changed Everything

On February 2, 1924, Reinhold and Emilia Gerber invited their family to dinner at their home just outside Albany. They were joined by their daughter Margaret Gerbig, her husband Paul, and their four young daughters — Hilda (10), Marie (7), Margaret (2), and little Esther (just 13 months old).

Paul’s sister Paula Ruhling, her husband Curt, and their son Horst also came, along with Hans Yunker, Emilia’s nephew.

It was the kind of gathering so many of us can picture — a multigenerational meal shared with laughter, stories, and food preserved with love. Among the dishes on the table that evening were home-canned green beans, put up earlier in the season.

But within hours, that warmth turned to alarm.

The Silent Killer in the Jar

Soon after dinner, several family members began feeling ill. Doctors were called, but there was little they could do. The symptoms spread rapidly — paralysis, difficulty breathing, and loss of speech — all signs of botulism, a rare but deadly form of food poisoning caused by the Clostridium botulinum bacteria.

Health officials later confirmed the beans had spoiled. They had likely been canned using a boiling-water or oven method, which was common at the time — and tragically, insufficient to destroy botulism spores in low-acid foods like beans.

In 1924, pressure canners were still new to the market, and many home preservers relied on inherited methods that simply couldn’t reach the temperatures needed for safety.

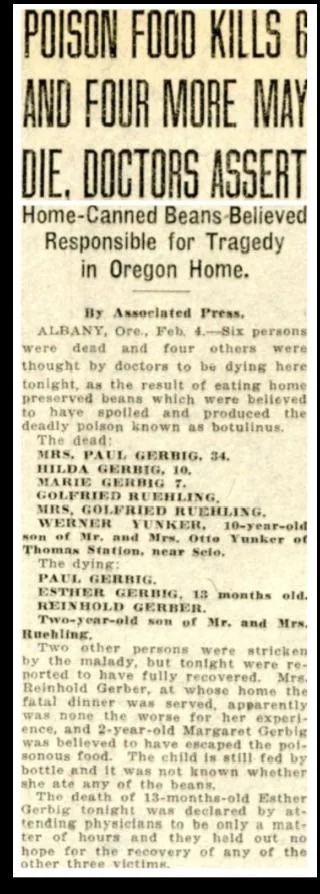

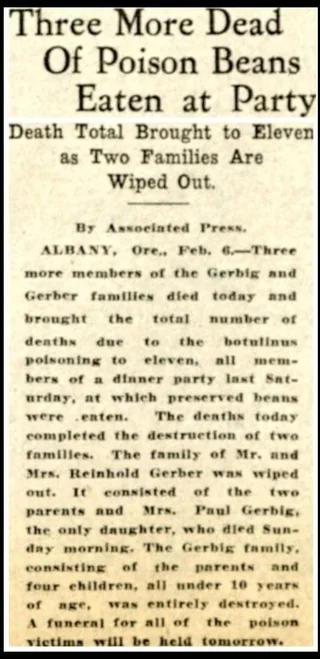

“Home-canned beans believed responsible for tragedy in Oregon home,” read one Associated Press headline.

“Three generations wiped out,” said another.

The Toll on One Family

Over the next several days, one by one, every person who had eaten the beans passed away.

By February 6, eleven were confirmed dead. A few days later, young Horst Ruhling also succumbed, bringing the death toll to twelve.

The joint funeral drew more than 1,500 mourners to the First Presbyterian Church in Albany — one of the largest gatherings the town had ever seen. Entire pews were filled with neighbors and farmers who had once shared garden surpluses, now grieving the loss of an entire branch of their community.

“The Gerber family, consisting of the parents and four children, all under 10 years of age, was entirely destroyed,” reported The Albany Democrat-Herald.

“The family consisted of the two parents and Mrs. Paul Gerbig, the only daughter, who died Sunday morning.”

Only distant relatives — Emilia’s brother Otto Yunker and his family — were left behind in the United States to mourn them.

Lessons Learned the Hard Way

At the time, most Americans had never heard of botulism. Many believed that if food looked and smelled fine, it was safe. Even more dangerous was the trust people placed in tradition — the way Grandma did it.

But Grandma didn’t know what we know now.

This tragedy helped change that. Health authorities, including Dr. Morris Fishbein of the American Medical Association, began a public campaign to educate home preservers on the importance of proper heat processing. Within a decade, pressure canners became standard in many kitchens, and government agencies began publishing tested canning recipes that remain the foundation of safe home preservation today.

What We Can Learn Today

It’s tempting to romanticize the old ways of canning — the stories of “nothing ever went wrong” or “we’ve always done it this way.” But food science has advanced for a reason. Botulism hasn’t disappeared; we’ve simply learned how to prevent it.

Here’s how you can honor that legacy safely:

- Use pressure canning for low-acid foods like beans, corn, and meats.

- Follow only tested recipes from trusted sources like the USDA, Ball, or your state extension office.

- Never alter acid levels or add oils to canning recipes unless they’re approved.

- Boil home-canned foods for 10 minutes before tasting if you ever suspect spoilage.

- When in doubt, throw it out.

Canning is one of the most rewarding homestead skills you can learn — but it’s also one that deserves respect.

A Legacy That Still Teaches

The Albany tragedy of 1924 stands as a painful but important reminder:

canning safely isn’t about fear; it’s about stewardship. It’s about protecting the ones who will sit at your table, just as the Gerbers once gathered around theirs.

Every jar you prepare with care, every time you double-check a recipe or reach for your pressure canner instead of the stockpot — you’re honoring those who didn’t have the knowledge we do now.

And that, more than anything, is the quiet power of learning from the past.

Sources:

Learn more at: